Fangs - The Jazz Project

Posted On: October 11, 2008 [Respond / Archives]

One of my great pleasures in life is discovering new jazz albums. I don't think I have to tell anyone who knows anything about jazz that major-label jazz is dead. No labored breathing, no last gasps, it's just gone. If you like the smooth suff . . . well, you can stick it in your Amazon cart along with the latest Britney Spears album in full confidence that there will be plenty more where that came from. But I haven't heard anything new on a major label that I really liked since Horace Silver's last album came out on Verve in 1999. Reissues? Well, now that the Blue Note and OJC catalogues have been pretty well exhausted, what remains might be interesting (Chess, Duke/Peacock, etc.) but I don't think there are any hidden Sidewinder's or Soul Station's left out there. (Unless you count Sonny Criss's At The Crossroads, which has been released in Japan.)

One of my great pleasures in life is discovering new jazz albums. I don't think I have to tell anyone who knows anything about jazz that major-label jazz is dead. No labored breathing, no last gasps, it's just gone. If you like the smooth suff . . . well, you can stick it in your Amazon cart along with the latest Britney Spears album in full confidence that there will be plenty more where that came from. But I haven't heard anything new on a major label that I really liked since Horace Silver's last album came out on Verve in 1999. Reissues? Well, now that the Blue Note and OJC catalogues have been pretty well exhausted, what remains might be interesting (Chess, Duke/Peacock, etc.) but I don't think there are any hidden Sidewinder's or Soul Station's left out there. (Unless you count Sonny Criss's At The Crossroads, which has been released in Japan.)

In some respects I've been very fortunate in that my Hard Bop site has been fairly popular. As a result I've received numerous copies of CDs I never would have stumbled across in a million years. Yoav Polachek's Standards First and Stacie McGregor's Straight Up came to me through eager press agents who were willing to send me promo discs. Both were fantastic and I have been effusive supporters of both on my site. But the most exciting revelation came with guitarist Jake Langley. As a fan for years of Grant Green and Kenny Burrell, I obviously wanted a younger representative of the hard bop guitar style on my site, and for a while I had to settle for Mark Whitfield, though I was never really enamored of his playing. All of that changed, however, when I stumbled across Doug's Garage in doing research for my book on Horace Silver. Jake Langley is the real deal, and why he is not yet a world-wide jazz phenomenon never fails to astound me.

All of which brings me to Fangs. A couple of years ago now, the oldest son of my best friend made me a CD with a variety of jazz things that he liked and wanted to share with me. One of them was an old Harold Mabern tune called "Rakin' and Scrapin'" that had a classic, late-60s Blue Note/Prestige tenor-and-organ sound. I naturally assumed it was one of the dozens of albums of that era that Prestige has been slowly leaking into the market, first in their gawd-awfully marketed "Legends of Acid Jazz" series and subsequently in less embarrasing two-fers. But no, it turned out that this was recent release by his saxophone teacher, Garry Hammond. I immediately bought a copy of it on CD Baby and could hardly stop listening to it. Fangs is, pure and simple, a great jazz album. But you don't need to take my word for it. Listen for yourself to Hammond's "Slightly In The Tradition" [mp3] and I dare you not to buy the album.

Red Rodney - Red Alert (Pt. 2)

Posted On: August 22, 2008 [Respond / Archives]

I didn't really learn about Red Rodney until after he was gone. Of course I knew of him through the Charlie Parker sessions on Verve (Swedish Schnapps, 1949), and especially the Carnegie Hall concert from 1949, which I felt was exceptional. But it wasn't until after seeing Clint Eastwood's biopic Bird that I began to seek out and listen to the music of "Albino Red."

I didn't really learn about Red Rodney until after he was gone. Of course I knew of him through the Charlie Parker sessions on Verve (Swedish Schnapps, 1949), and especially the Carnegie Hall concert from 1949, which I felt was exceptional. But it wasn't until after seeing Clint Eastwood's biopic Bird that I began to seek out and listen to the music of "Albino Red."

At the time there was very little of his fifties material on CD, and mostly what was available were later 70s and 80s sessions, some of them great--Bird Lives! with Charles McPherson on alto--and some not so great--Red Alert!. There was, however, through all of his playing, the link with Charlie Parker that was undeniably appealing. One of my favorite memories was listening to a cassette tape I had of Parker's Washington D.C. big band recording and hearing Red's voice come on at the end: "Now, this Washington date . . ." [mp3] And I've always appreciated and enjoyed the fact that it's Red himself who can be heard playing on "Now's the Time" from the Bird Soundtrack. None of that, though, prepared me for the brutal truth about his life as told to Gene Lees in his book Cats Of Any Color. Easily one of my favorite books on jazz, it's well worth seeking out.

Though most of the recordings done late in his career are wonderful, I was most interested in the early dates for Prestige and Keystone. Then, I happened on a 2001 release of two dates from Chicago, one in 1951 and the other in 1955, both on a single CD entitled Red Rodney Quintets. Featuring original bop tunes and standards, it's a great example of the music before Parker's death. In spite of the title of the disc, "The Song is You" [mp3] from the later session is all Red. Great music from one of the all time greats, and hopefully not the last of his earlier recordings to be reissued. The ultimate tribute, for which Red seems like a perfect candidate, would be a Mosaic box set. Let's hope it happens soon.

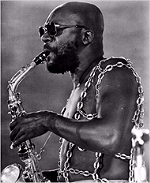

Isaac Hayes

Posted On: August 13, 2008 [Respond / Archives]

I've been spending so much time watching the Olympics the past few days that I didn't learn until Wednesday of the passing of Isaac Hayes. Of course, being relatively young, my first exposure to Hayes didn't come until the 70s in high school, playing the "Theme from Shaft" in the pep band. Even so, I wasn't actually conscious of the Black Moses until I began examining the composer credits on my Sam & Dave albums. It wasn't long after that Stax became my favorite record label, and Hayes one of my favorite musicians. The soundtrack to Shaft is still one of my favorite albums . . . ever . . . in any genre.

I've been spending so much time watching the Olympics the past few days that I didn't learn until Wednesday of the passing of Isaac Hayes. Of course, being relatively young, my first exposure to Hayes didn't come until the 70s in high school, playing the "Theme from Shaft" in the pep band. Even so, I wasn't actually conscious of the Black Moses until I began examining the composer credits on my Sam & Dave albums. It wasn't long after that Stax became my favorite record label, and Hayes one of my favorite musicians. The soundtrack to Shaft is still one of my favorite albums . . . ever . . . in any genre.

There have been numerous versions of Isaac Hayes' "Theme from Shaft" but I wanted to share with you one of my favorites. It's from the 1972 album by Maynard Ferguson MF Horn 2. In terms of fusion/big band sessions from the 70s, this has to be near the top of the list in terms of both song selection and solos. The opener, "Give It One," is probably the best Ferguson track from the entire decade. The Shaft theme [mp3] is great not only because of the unique arangement by Keith Mansfield, but also the funky piano by Pete Jackson, gritty alto solo by Jeff Daly, and a valve trombone solo by Ferguson himself. Although, having a great tune to cover is what finally makes it all come together.

One of my favorite stories about Hayes was how, in the old days at Stax, they used to double-book Booker T. & the M.G.s into two clubs on the same night. Booker would go out with the second-string rhythm section--some of whom would go on to form the Bar-Kays. And at the other show would be Al Jackson, Duck Dunn, and Steve Cropper along with--you guessed it--Isaac Hayes at the organ. Isaac Hayes was a tremendous talent and a real driving force in soul music, especially the transition into the 1970s, and he'll be missed by many.

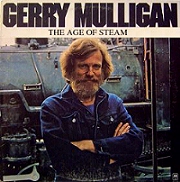

Gerry Mulligan - Age of Music Blogs

Posted On: August 1, 2008 [Respond / Archives]

If you read my earlier post on Blue Mitchell, then you know of my recent reassessment of the fusion period of jazz in the 1970s. The proliferation of music blogs and the ability to sample much of the music before searching out a hard copy has been a real boon to the expansion of my musical tastes. I mean, let's be truthful here, sixty-second samples of jazz tunes on any retail site are almost worthless. In most instances the sample either begins with the head and we hear none of the solos, or the sample begins in mid-solo and we have no idea of the context (or the other soloists). It's never been a worthwile expenditure of time. Therefore, the purchase of CDs has always come down to familiarity. And while the fear of buying something you hate has diminished with availability of sites like eBay or Half.com to unload clunkers, there is still the disappointment factor and the feeling of getting burned that keeps me coming back to the tried and true. Another Lee Morgan or Hank Mobley reissue? Great, toss it in the basket. But once you have every Blue Note and OJC reissue, what's next?

If you read my earlier post on Blue Mitchell, then you know of my recent reassessment of the fusion period of jazz in the 1970s. The proliferation of music blogs and the ability to sample much of the music before searching out a hard copy has been a real boon to the expansion of my musical tastes. I mean, let's be truthful here, sixty-second samples of jazz tunes on any retail site are almost worthless. In most instances the sample either begins with the head and we hear none of the solos, or the sample begins in mid-solo and we have no idea of the context (or the other soloists). It's never been a worthwile expenditure of time. Therefore, the purchase of CDs has always come down to familiarity. And while the fear of buying something you hate has diminished with availability of sites like eBay or Half.com to unload clunkers, there is still the disappointment factor and the feeling of getting burned that keeps me coming back to the tried and true. Another Lee Morgan or Hank Mobley reissue? Great, toss it in the basket. But once you have every Blue Note and OJC reissue, what's next?

What the music blog allows me to do differently, is to listen to the entire album, in context, and then decide if this is something I'd like to have in my collection, with art, liner notes, etc. It's because of this that I have recently not only purchased a bunch of fusion CDs, but also a batch of West Coast and avant-garde sessions that I never would have glanced at in the old days while looking through the racks at Tower Records or Borders. Combining these new (to me) spheres of music is an LP that I find absolutely wonderful: Gerry Mulligan's The Age of Steam. For one thing--and probably the most important--this session finds Mulligan abandoning his effete counterpoint for a more robust style that is incredibly satisfying. For another, he shares solo duties equally with the other members of the group: Bob Brookmeyer, Roger Kellaway, Tom Scott, and Stephen Goldman. Great music, and great solos, with the Fender Rhodes about the only thing that dates it in any way: "Maytag" [mp3]

But it gets better. The DVD of Age of Steam has a fantastic documentary Listen: Gerry Mulligan, a section with Gerry himself leading viewers through a master class, other contributors to his album giving interviews, lead sheets to the tunes and a ton of other stuff. In addition, the DVD also comes with a copy of the CD--for the price, it's a nice set. Not only has this become a satisfying addition to my DVD music library, more importantly, I never would have looked twice at it had I not been able to download the album first from a music blog. And while there are plenty of albums that we all have that we don't like well enough to buy but don't hate enough to delete, the music blog serves an important function that I hope is allowed to continue for a long time.

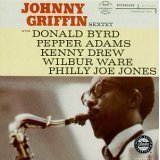

Johnny Griffin

Posted On: July 27, 2008 [Respond / Archives]

The attrition of jazz greats continued Friday with the passing of Johnny Griffin. The oft-proclaimed "fastest saxophonist in the world" also had one of the world's greatest careers. From his first sessions on Blue Note, a stint with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, to a lengthy residence at Riverside, recording sessions with all the greats, and eventual ex-patriat status in France, Griffin continued to play his effervescent brand of hard bop right up to the end. The death of Johnny Griffin is also a sobering reminder of the precarous position of jazz in America as the numbers of great players dwindles even further and its presence on major record labels is all but non-existent.

The attrition of jazz greats continued Friday with the passing of Johnny Griffin. The oft-proclaimed "fastest saxophonist in the world" also had one of the world's greatest careers. From his first sessions on Blue Note, a stint with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, to a lengthy residence at Riverside, recording sessions with all the greats, and eventual ex-patriat status in France, Griffin continued to play his effervescent brand of hard bop right up to the end. The death of Johnny Griffin is also a sobering reminder of the precarous position of jazz in America as the numbers of great players dwindles even further and its presence on major record labels is all but non-existent.

My favorite session of Griffin's has always been the Johnny Griffin Sextet for Riverside with the Donald Byrd--Pepper Adams Quintet. Not only are the songs great, but the solos are excellent and the sound quality is better than usual for a Riverside LP. While all of the independent labels used Rudy Van Gelder's studio back then, the Riverside sessions often used other studios and therefore never had the big, open sound of the Blue Note or Prestige from the same time. The opening track, "Stix Trix" [mp3] is the highlight for me. Written by drummer Wilbur Campbell, the tune first appeared on the LP Nicky's Tune by Ira Sullivan recorded in Chicago--Griffin's home town--by the title "Wilbur's Tune." That was something Griffin also liked to do, use tunes by fellow Chicagoans on his albums, like "Latin Quarters" by John Jenkins which Griffin used on his Blue Note session The Congregation in 1957 and then again with the composer on the Wilbur Ware session The Chicago Sound.

Griffin's sextet session comes just a few months after his association with Blue Note ended. Other tunes include a Griffin original entitled "Catharsis," the Burke-Haggart standard "What's New," and an interesting quartet take of Dizzy Gillespie's "Woody'n You." What's interesting about the arrangement is how Griffin--as the only horn--plays the counterpoint to the melody instead of the melody itself. The genesis of this would seem to be the Coleman Hawkins' version from 1944. With Hawkins front and center at the mike, Gillespie's melody statement can barely be heard in the background. It is undoubtedly this "mistake" that Griffin emulated on tune, and to pleasing effect.

Griffin's sextet session comes just a few months after his association with Blue Note ended. Other tunes include a Griffin original entitled "Catharsis," the Burke-Haggart standard "What's New," and an interesting quartet take of Dizzy Gillespie's "Woody'n You." What's interesting about the arrangement is how Griffin--as the only horn--plays the counterpoint to the melody instead of the melody itself. The genesis of this would seem to be the Coleman Hawkins' version from 1944. With Hawkins front and center at the mike, Gillespie's melody statement can barely be heard in the background. It is undoubtedly this "mistake" that Griffin emulated on tune, and to pleasing effect.

The other session I would like to mention is a live concert from France that was recorded in 1989 on the LP Birdology. With fellow bebopers Jackie McLean, Cecil Payne, Duke Jordan and Roy Haynes, it is a masterful tribute not only to Charlie Parker, but to the musical prowess of all involved. The "Little Giant" was truly one of the tenor giants of his day. Along with John Coltrane and Hank Mobley he defined the hard bop tenor sound of the 1960s, specifically the Chicago style heard in other tenors like Clifford Jordan and John Gilmore, and his edgy, frenetic playing on countless recording sessions over the past five decades will be treasured as long as the music survives.

Blue Mitchell - Fun With Fusion

Posted On: July 26, 2008 [Respond / Archives]

If you had told me a year ago that I would have a genre on my iPod called "Fusion" I'd have told you you were crazy. While I like a good soul jazz album as much as the next person (Jimmy Smith, Lonnie Smith, Houston Person, Boogaloo Joe Jones, et al.) once you start adding strings and vocals, that's where I draw the line. Unfortunately, it's the worst examples of fusion that tend to be the ones record companies make available to us in great numbers (Kenny G., Kirk Whalum, Tom Scott, et al), and in any case I've always found that a little Crusaders can go a long way. But recently, with the proliferation of music blogs like My Jazz World, such an incredible number of fusion albums have been made available to the public that it forced me into a re-examination of the whole genre.

If you had told me a year ago that I would have a genre on my iPod called "Fusion" I'd have told you you were crazy. While I like a good soul jazz album as much as the next person (Jimmy Smith, Lonnie Smith, Houston Person, Boogaloo Joe Jones, et al.) once you start adding strings and vocals, that's where I draw the line. Unfortunately, it's the worst examples of fusion that tend to be the ones record companies make available to us in great numbers (Kenny G., Kirk Whalum, Tom Scott, et al), and in any case I've always found that a little Crusaders can go a long way. But recently, with the proliferation of music blogs like My Jazz World, such an incredible number of fusion albums have been made available to the public that it forced me into a re-examination of the whole genre.

The fact that for decades the CTI catalog has been the most visible (read avalable) fusion on the market has done a real disservice to everyone, from the record companies right down to the consumer. In the first place, I find the CTI sessions the least compelling fusion albums that I've heard over the last year. Just one example of this phenomenon is the great Blue Mitchell. After his tenure with Riverside in the early sixties, he signed with Blue Note when he and Junior Cook were let go of the Horace Silver quintet. After some terrific quintet albums he recorded a couple of funky big-band type sessions before his first out-and-out fusion session, Bantu Village, in 1969. After that, he recorded sessions for a number of labels (Impulse, Roulette, RCA) that are notable for their incredible consistency of quality jazz--albeit in a fusion style. Which means, if you hate Isaac Hayes, Booker T., and The Crusaders, you're probably going to hate these records too. But . . . if you've secretly kept all of your Blackbyrds, John Klemmer, and Maynard Ferguson vinyl, you'll LOVE Blue Mitchell's fusion sessions.

The thing that makes these sessions so great are the players, from pop/fusion stallwarts like Chuck Rainey and Lee Ritenour to hard bop greats like Harold Land, Cedar Walton, Hampton Hawes, and Eddie Harris. The solos are fantastic, and to lump these kinds of sessions in with no-talend smooth jazz of the last thirty years borders on the criminal. The only one of Mitchell's sessions that is available on CD is, of course, not one of his best. Though Graffiti Blues is a worthy pickup, my favorite album is Stratosonic Nuances with the great Harold Land on tenor and Cedar Walton on electric piano. But there is equally great music to be had elsewhere, as evidenced by this cover of Horace Silver's "Peace" [mp3] on the Roulette album Last Tango Blues.

The thing that makes these sessions so great are the players, from pop/fusion stallwarts like Chuck Rainey and Lee Ritenour to hard bop greats like Harold Land, Cedar Walton, Hampton Hawes, and Eddie Harris. The solos are fantastic, and to lump these kinds of sessions in with no-talend smooth jazz of the last thirty years borders on the criminal. The only one of Mitchell's sessions that is available on CD is, of course, not one of his best. Though Graffiti Blues is a worthy pickup, my favorite album is Stratosonic Nuances with the great Harold Land on tenor and Cedar Walton on electric piano. But there is equally great music to be had elsewhere, as evidenced by this cover of Horace Silver's "Peace" [mp3] on the Roulette album Last Tango Blues.

Why, in this day and age, record companies can't make all of their sessions available as downloads is beyond me. I understand them not wanting to put out money and time to produce all of those lost sessions on CD, but it can't take that much effort to make albums available on iTunes, or similar sites. Fortunately, most of those lost albums are out there if you do a bit of searching. So, if you enjoy the occasional Wah-Wah pedal guitar, thumb-slapping bass, and Fender Rhodes piano, check out some of the many music blogs out there offering up hundreds of 70s fusion albums--albums that also happen to contain some fantastic jazz solos by the sixties hard bop greats who, it turns out, never really stopped playing after all.

Cecil Payne - BeBop Baritone

Posted On: July 18, 2008 [Respond / Archives]

When I was in eighth grade I was invided to join the Jr. High jazz band after only two years of playing alto sax. What surprised me most was that the band director wanted to allow one of the clarinet players to switch to alto and have me play the baritone sax. Not only was I not offended, I was fascinated by the big, school horn I was given and found the lower register quite appealing--not to mention the parts significanly easier to play. Ever since that time I've been in love with the bari sax. So it should be no surprise then, that one of the first jazz CDs I ever purchased was by the late, great, Cecil Payne.

When I was in eighth grade I was invided to join the Jr. High jazz band after only two years of playing alto sax. What surprised me most was that the band director wanted to allow one of the clarinet players to switch to alto and have me play the baritone sax. Not only was I not offended, I was fascinated by the big, school horn I was given and found the lower register quite appealing--not to mention the parts significanly easier to play. Ever since that time I've been in love with the bari sax. So it should be no surprise then, that one of the first jazz CDs I ever purchased was by the late, great, Cecil Payne.

What was a surprise for me, though, what just how great Payne was. Not only could he navigate effortlessly on the big horn, but did so playing some of the most challenging music ever: straight-ahead bebop. Like fellow saxophonist Sonny Stitt, Cecil Payne played bebop his entire career, an unabashed exponant of Charlie Parker's legacy. Payne's most definitive statement came early on in his lengthy career. The two sessions that comprise Patterns of Jazz on Savoy Records. Recorded in 1956, just a year after Parker's death, they are nothing short of stunning. The first session is a quartet, with Duke Jordan on piano and Tommy Potter on bass (both recently with Parker's band), in which Payne performs tunes associated with Parker, including "This Time The Dream's On Me," and "How Deep Is The Ocean" in addition to two distinctive originals. The second set adds yet another Parker sideman, Kenny Dorham on trumpet. Three more infectious Payne originals lead off this session with highlight of the entire album being Payne's solo opening to "Man of Moods" [mp3]. Fittingly, the album ends on a high note with Dizzy Gillespie's "Groovin' High."

Cecil Payne would appear on countless sessions in the fifties and sixties, on albums as diverse as Kenny Dorham's Afro-Cuban and Jimmy Smith's Six Views of the Blues on Blue Note, John Coltrane's Dakar on Prestige and Clark Terry's self-titled debut [Clark Terry] on EmArcy. He was one of the all-time great jazz musicians--on any instrument--and continued to appear on quality albums and tour throughout the 70s, 80s, and 90s. Cecil Payne passed away just last November and he is greatly missed.

I'll never forget the day a few years ago when I was looking through a friend's stack of old magazines and happened upon a review for the closing of Birdland back in the late 70s. The author was lamenting the sorry state of the club--having been turned into a disco a few years earlier--and at the same time the sorry state of jazz, in that none of the musicians assembled to pay tribute to the namesake of the club actually played bebop . . . except for one, and that musician was Cecil Payne.

Red Garland - Red Alert!

Posted On: July 1, 2008 [Respond / Archives]

Until recently I had always associated Red Garland's piano playing with Miles Davis's rather stodgy attempts at hard bop, and his emphasis on block-chording in that context rather than single-note lines never really grabbed me. But my attitude toward Red changed when I picked up a copy of Phil Woods' Sugan. I already had a couple of Garland albums with John Coltrane, but they seemed a bit more subdued as well, tending toward slow, blues numbers. The set with Woods and trumpeter Ray Copeland is a no-frills Prestige blowing session, but seems to have nonetheless been an inspired date that surpasses the usual rote playing that figures into a lot of those kinds of sessions by both Woods and Garland.

Until recently I had always associated Red Garland's piano playing with Miles Davis's rather stodgy attempts at hard bop, and his emphasis on block-chording in that context rather than single-note lines never really grabbed me. But my attitude toward Red changed when I picked up a copy of Phil Woods' Sugan. I already had a couple of Garland albums with John Coltrane, but they seemed a bit more subdued as well, tending toward slow, blues numbers. The set with Woods and trumpeter Ray Copeland is a no-frills Prestige blowing session, but seems to have nonetheless been an inspired date that surpasses the usual rote playing that figures into a lot of those kinds of sessions by both Woods and Garland.

Three of the tunes are by Charlie Parker and it's there where the stength of set lies--and also its superiority in comparison with similar dates. One in particular I'm thinking of is another Phil Woods bebop date produced by Leonard Feather entitled Bop!. Recorded only a month after Sugan, it seems especially tired and forced (in the way most Feather sessions were--this one featuring Parker's son shouting out an atonal "Salt pea-nuts! Salt pea-nuts!"). On the earlier session Woods seems bright and energetic on "Au Privave," [mp3] "Steplechase" and "Scrapple from the Apple." And, of course, Garland's spot-on accompaniment holds the proceedings together extremely well. One of the real treats, however, is Ray Copeland's trumpet work. Much more appropriate than Thad Jones' work on the Feather session, it nearly equals that of Carmel Jones on arguably the best of the post-bop retrospective albums ever recorded: Charles McPherson's Bebop Revisited. Finally, there are also three Woods-penned numbers that have more of a hard bop feel to them, the best being the title track.

Sparking a renewed interest in Red Garland, I have recently obtained several more discs of his and have been enjoying them all. And while I find his piano trios less interesting that say, Elmo Hope, or Ray Bryant's, many of his larger groups are quite good, the ones with Coltrane, of course, but also a terrific sextet date on Jazzland with Pepper Adams and Blue Mitchell called Red's Good Groove that contains his signature block-chord work rather than the more bopish lines of the Wood date, but does sound better than many Riverside sextet sessions from the same era. Way to go, Red.

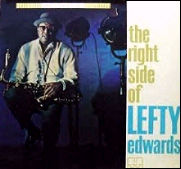

Motown Jazz?

Posted On: June 26, 2008 [Respond / Archives]

Of course we all know that there was great Hard Bop in Detroit. The list of names speaks for itself, Barry Harris, Hank, Elvin, and Thad Jones, Pepper Adams, Kenny Burrell, Curtis Fuller, Donald Byrd, Frank Foster, etc. But even as a die-hard-bop fan I was surprised to learn, on one of my forays through cyberspace, that Berry Gordy at Motown released eleven albums of jazz on one of his subsidiary labels. As Mr. Spock would say . . . fascinating.

Of course we all know that there was great Hard Bop in Detroit. The list of names speaks for itself, Barry Harris, Hank, Elvin, and Thad Jones, Pepper Adams, Kenny Burrell, Curtis Fuller, Donald Byrd, Frank Foster, etc. But even as a die-hard-bop fan I was surprised to learn, on one of my forays through cyberspace, that Berry Gordy at Motown released eleven albums of jazz on one of his subsidiary labels. As Mr. Spock would say . . . fascinating.

To date I've listened to about eight of them and, while the musicianship is good, the recording quality is woefully inadequate, especially on the trio albums by pianist Johnny Griffith (not Griffin). Pianist Earl Washington fares a bit better on his albums. Trombonist George Bohanon's bossa nova album is far more bop than latin--a good thing IMHO--and there is a Jonah Jones LP that leans a bit too much in the Pete Fountain/Al Hirt faux jazz direction for my taste. But the real find is the set by alto/tenor saxophonist Lefty Edwards. Again, the recording is poorly done, but the music is fantastic. If only he'd been in New York with Rudy VanGelder, this one would probably have been a classic. On a set of mostly standards, Edwards shows a distinctive Frank Foster style, easily mixing swing and bop phrasing. The standout track for me is his interpretation of "Goodnight, My Love" [mp3], his double-time work on the alto bringing instantly to mind Sonny Stitt.

Evidently Berry Gordy was able to entice some of the remaining local jazz musicians in Detroit to come and play on Motown sessions by offering them recording sessions of their own on the Motown Jazz label. It would be nice to see if someone could take the master tapes--assuming they still exist--and clean them up for CD reissue. Until then you can find the LPs on the fullundie music blog. While maybe not keepers, worth a download or two.

Dinah Washington

Posted On: June 23, 2008 [Respond / Archives]

Though she'll always be know as the Queen of the Blues, I'm not shy about making the argument for Dinah Washington as one of the all-time great jazz singers. Certainly she's always been my favorite. Sure, she doesn't have the range and musicality of Sarah Vaughn, or the fragile intangible that is Billie Holiday. What she does possess, however, is a swaggering confidence in her own abilities that that threatens, at times, to overshadow the song itself. Rather than than finger-in-her-dimple ebullience of Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah isn't afraid to put one hand firmly on her hip and with the other to wag that finger right in your face.

Though she'll always be know as the Queen of the Blues, I'm not shy about making the argument for Dinah Washington as one of the all-time great jazz singers. Certainly she's always been my favorite. Sure, she doesn't have the range and musicality of Sarah Vaughn, or the fragile intangible that is Billie Holiday. What she does possess, however, is a swaggering confidence in her own abilities that that threatens, at times, to overshadow the song itself. Rather than than finger-in-her-dimple ebullience of Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah isn't afraid to put one hand firmly on her hip and with the other to wag that finger right in your face.

The voice is really the thing, though. At once nasal and lacking in dynamics, it is also the most sublime of instruments, in the same way that blues shouters from Jimmy Rushing and Joe Williams to soul-men like Lou Rawls and Ray Charles have been able to make incredibly fine jazz albums. While Dinah began her jazz in less than stellar form, beginning with risqué blues numbers backed by the Lucky Thompson and Illinois Jacquet orchestras, then working through dreary string and chorus-ladened Mitch Miller arrangements, she found her form on her mid-fifties EmArcy sessions.

The pinnacle of this era is easily her 1955 session For Those In Love. Joining her is an especially sympathetic group of musicians including Clark Terry, Jimmy Cleveland, Paul Quinchette, Cecil Payne, and Wynton Kelly. With arrangements by Quincy Jones it is a sterling performance. One jazz classic after another is reeled off by Washington with what are arguably definitive performances of Cole Porter's "I Get A Kick Out Of You," and the Rodgers-Hart "I Could Write A Book." But the gem of the session is, without a doubt, her haunting performance of "You Don't Know What Love Is."

One year earlier Dinah was in the studio with an augmented Brown-Roach unit (Clifford Brown, Harold Land, Junior Mance, George Morrow and Max Roach) to record Dinah Jams, a live-in-the-studio LP for EmArcy that I have samples of to whet your appetite for my own personal "Queen of Jazz." The first is a classic example of her ballad delivery on "Come Rain or Come Shine" [mp3], wonderfully robust and vulnerable at the same time-with a gospel "hallelujah" middle chorus that elicits hollers and applause from the studio audience. The second is an equally explosive "There Is No Greater Love" [mp3], with a trumpet-like smear that turns the notion of a ballad being soft on its head. Check out some of her work on EmArcy and see if Dinah doesn't turn your head as well.

One year earlier Dinah was in the studio with an augmented Brown-Roach unit (Clifford Brown, Harold Land, Junior Mance, George Morrow and Max Roach) to record Dinah Jams, a live-in-the-studio LP for EmArcy that I have samples of to whet your appetite for my own personal "Queen of Jazz." The first is a classic example of her ballad delivery on "Come Rain or Come Shine" [mp3], wonderfully robust and vulnerable at the same time-with a gospel "hallelujah" middle chorus that elicits hollers and applause from the studio audience. The second is an equally explosive "There Is No Greater Love" [mp3], with a trumpet-like smear that turns the notion of a ballad being soft on its head. Check out some of her work on EmArcy and see if Dinah doesn't turn your head as well.

Max Roach

Posted On: August 16, 2007 [Respond / Archives]

One of the all-time greats passed away today, Max Roach, the brilliant drummer, composer, activist and educator. My first exposure to Max was on Charlie Parker's recordings. What struck me immediately was the incredible precision of his playing. Unlike other boppers like Bud Powell and even Dizzy Gillespie who could, at times, sound very sloppy, Max's playing always seemed crisp and precise--like Bird himself. But it was his recordings with Clifford Brown, and the introduction to Max's melodic style of drumming, that won me over.

One of the all-time greats passed away today, Max Roach, the brilliant drummer, composer, activist and educator. My first exposure to Max was on Charlie Parker's recordings. What struck me immediately was the incredible precision of his playing. Unlike other boppers like Bud Powell and even Dizzy Gillespie who could, at times, sound very sloppy, Max's playing always seemed crisp and precise--like Bird himself. But it was his recordings with Clifford Brown, and the introduction to Max's melodic style of drumming, that won me over.

In 1990 I had the good fortune to see the Max Roach Quartet with trumpeter Cecil Bridgewater and saxophonist Odean Pope at Seattle's Jazz Alley. Again, what impressed me the most was his melodic approach to the drums. Now, while the drums in bebop had been liberated from mere timekeeping since WWII, there were few drummers who took advantage of that fact in the way that Max did. Unlike most drum solos where musicians need to count measures in their head to know when to come back in, Max would always keep the melody in the forefront of his playing. Even when stretching out, in the same way you can hear the underlying chords in a melody instrument's solo, you could hear the melody amid his percussion improvisiation. Check out "Drum Conversation" [mp3] from 1953.

My favorite albums among Max's work are the the two albums with Clifford Brown titled Study In Brown and More Study In Brown. I also really enjoy his disc with Hank Mobley on Chess records simply titled Max, and of course the disc with Sonny Rollins and Kenny Dorham that he recorded shortly after Brownie's death, Max Roach Plus Four